ceo chats

Tackling Female

Genital Mutilation with Tech

By Linda Nguyen and Jessica Czarnecki

Reading time: 10 minutes

Big, Bold Ideas:

Stacy Owino remembers the moment she found out about female genital mutilation (FGM).

She was in elementary school in Kenya when she saw a news story about a girl who had undergone FGM, a cultural ritual that involves cutting or removing some or all female genitalia.

“It was so harrowing, and I didn’t understand why anyone would have to go through this,” she recently told Plan International Canada CEO Lindsay Glassco.

“It stuck in my head because I was almost the same age as her [the girl who was cut] back then, so I thought, ‘This could have been me if I came from that community.’”

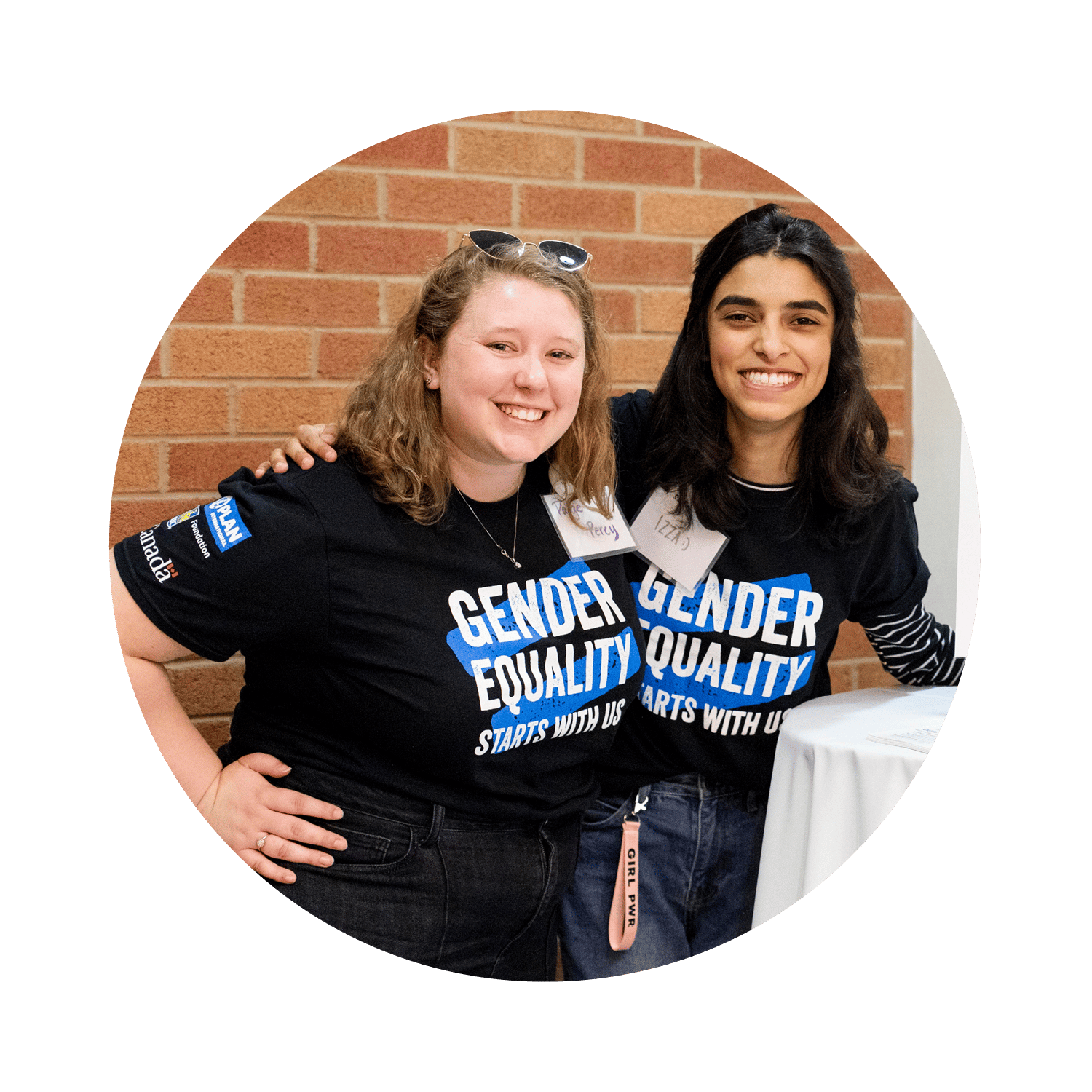

Youth activist Stacy Owino shares big, bold ideas with Plan International Canada CEO Lindsay Glassco on how technology can protect girls from female genital mutilation in Kenya.

How prevalent is FGM?

This is the first interview in our new series, CEO Chats: Big, Bold Ideas for a Brighter Tomorrow, where Plan International Canada CEO Lindsay Glassco speaks with some of the brightest young people from around the world striving to make the future a safer, sustainable and equal place for all. #UntilWeAreAllEqual

Join us again in December when we’ll post Lindsay’s conversation with award-winning Canadian actor and human rights youth advocate Saara Chaudry.

According to UNICEF, more than 200 million girls have undergone FGM in 30 countries across Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

On average, girls are between 7 and 10 when they’re cut, but some are subjected to FGM when they are babies. Female genital mutilation, which has been illegal in Kenya since 2001, is a form of gender-based violence and a violation of women’s and girls’ fundamental human rights.

Despite this, it is still often done in secret and unsafe conditions. The practice persists for different reasons. Sometimes it’s considered a rite of passage or a way to control a girl’s sexuality. In some communities, it is required before marriage.

Girls who undergo FGM can suffer from physical injury, severe bleeding, problems urinating, cysts, infections, complications during childbirth and an increased risk for newborn deaths. It’s estimated that medical treatment for complications resulting from FGM costs US$1.4 billion a year globally.

In Owino’s conversation with Plan International Canada CEO Lindsay Glassco, she shared why the app is needed, why it has been so hard to go up against this traditional practice and the important role women can play in tech.

Here are some edited highlights from their conversation.

Stacy Owino (far right), with the other co-developers of the iCut app. They call themselves “The Restorers” and created the app to raise awareness and fight female genital mutilation in Kenya.

How the iCut app works

The iCut app:

Features a distress button that connects the user with someone on the phone (police, hospital, local activists) or allows them to send a message to report expected incidents of FGM

Lindsay

Q: You’ve played a significant role in helping prevent FGM and to change cultural norms around it. Have you heard from girls and women who have used your app?

Stacy

A: We sat down with women and girls to hear their stories. Many told us they expect their daughters to undergo FGM because that’s what their mothers went through, their grandmothers and so on. So we realized we had to demystify this and break the chain.

Q: Incredible. Turning ideas into tangible actions is always a tremendous accomplishment, but it’s never as simple as one thinks. Did you face any backlash?

A: Yes. After we won [the global Technovation Challenge], a man came to our school – please remember, I was only 17, and this was a girls’ boarding school – and he demanded that we stop developing the app. He claimed we didn’t know what we were talking about or anything about the culture. From then on, we knew we were tackling a social issue.

Q: Did you have any mentors or role models who helped you develop the app?

A: I was about to play handball when my computer studies teacher suggested I stay for a presentation about the Technovation challenge. The lady giving the presentation introduced us to mentors from the program. I met with a woman pursuing a mathematics and computer science degree who interested me in the challenge.

Q: Have you seen a shift in how families and communities view FGM? If not, what more can be done?

A: Yes, I’ve seen change because of all the work of amazing FGM activists in Kenya and globally. What needs to happen is for more established organizations to work closely with grassroots organizations to get better access to funding and streamline the process to make it easier for those young, less-established organizations to get in and work toward a better future.

Q: That’s excellent advice, not to be divisive and always apply empathy so that you understand where the resistance is coming from. As you’ve said, change comes slowly, and if you don’t find innovative ways of bringing people into the conversation, it can be incredibly challenging.

A: It has become clear if we make it an “us-versus-them” type of conversation, then it’s an argument. Instead, you should bring it up as a collective community discussion. There can even be fun ways of doing it – like for the International Day of the African Child, we’re just talking about our values as Africans. How you bring it up and package it matters. It should be very empathetic so that it’s not a heated conversation but a soft discussion.

Q: It takes a lot of courage to speak out against traditional practices and beliefs like FGM, and pushback is often one of the reasons many people choose not to act on their ideas. Do you consider yourself an activist? What advice do you have for youth who want to speak up?

A: Yes, I do consider myself an activist. As an activist, it’s very important to have empathy, because this is how we’ll talk about and address these issues.

Q: What does it mean to be a youth leader?

A: For me, it’s very important to have diverse voices when in positions of power, because these people dictate how much money is allocated to which issues, both locally and internationally. We need more voices of African youth, especially young African women, to advocate for youth-friendly policies and to hold leaders accountable.

Stacy Owino on the girls she has helped with her app

Q: I love your dedication to social justice, your overall outlook on collaboration and how to make things scalable. I’m eager to know, what’s next for you?

A: It’s definitely the beginning. I just graduated in July, so I’m very open to new opportunities. One thing that has caught my heart is the intersection of tech, human rights and policies and how to make these three entities cohesive.

I want to do more schooling so I can understand social sciences better. I also want to get more involved in policy. My two years as one of the 25 members of the European Union’s Youth Sounding Board were incredible, and I feel the policy space is somewhere I belong. So, in the coming years, I think I’ll be in that space and working toward some social good.

Q: Wonderful. Stacy, this has been such an insightful conversation. I’m so grateful for this opportunity to learn more from you and hear about this important issue that still affects millions of girls and young women worldwide. I hope that we’ll hear more from you.

A: A huge thank you to Plan International Canada for extending this invite. I think it’s very important to talk about FGM continuously because statistics show that half a million girls in Kenya are at risk of undergoing FGM before 2030. If we think about these numbers as people and not just arbitrary figures, it calls for more empathy to accelerate this fight.

Stacy Owino’s advice to other youth activists

The youth behind the iCut app

When Owino was 17, she participated in the 2018 Technovation Challenge, a global competition to address social issues using technology. She and four other students wanted to create an app related to FGM – what it is, why it’s practised, its effects and the communities’ outlooks – and look for ways to solve it.

Stacy developed the iCut app with co-developers Cynthia Otieno, Purity Achieng, Macrine Atieno and Ivy Akinyi. Today, it has hundreds of downloads from the Google Play store and helps protect girls and young women in Kenya.

The developers call themselves “The Restorers,” because they want to restore hope to girls who are at risk and provide a safe way for them to contact authorities about FGM – and for the authorities to contact them.

Provides a list of services (rescue centres, police stations, health services) to users based on their location

Provides information on FGM, where and why it’s practised and the risk it poses to girls and women

Has a “Donate” button to support local organizations fighting FGM

Stacy Owino on why female leadership is so important

(Above) Stacy Owino at a speaking engagement about her app, iCut, which is being used to fight female genital mutilation in Kenya.

Meet Poria, a young woman in Kenya, who says education is helping save girls from FGM.

read more

Learn more

Why youth

activism matters.

read more

Why access to technology should be a right, not a privilege – especially for girls.

Three ways to support youth activism with

Girl Power

Tech Entrepreneurship for Women and Girls

Digital Safe Spaces for Girls

Gifts of Hope

This gift is matched

This gift is matched

This gift is matched

8x

4x

5x

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Stacy Owino on why female leadership is so important

Stacy Owino shares the difference the app has made.

When we gave women information [about the harms of FGM], they told us that if they had known beforehand, they wouldn’t have [subjected their daughters to FGM]. The overall feedback was that the app was convenient and could help eradicate female genital mutilation in the region.