Find out more

Lorem tore veri tatis et quasi archi te cto heys esbe.

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem qui

Share this article

John Smith

"Add in a really fun quote here with a great fact or entertaining insight or data point! "

In a recent essay on Harvard’s Nieman Lab, Rebecca Rozelle-Stone, a professor of philosophy at the University of North Dakota, writes that to fight news fatigue, we need to regain some degree of “moral attentiveness” instead of just tuning out. She recommends that journalists offer more “solutions-based stories that capture the possibility of change” and that the rest of us limit our intake of catastrophe-led daily news and instead turn to long-form articles and essays that offer more depth and understanding in their reporting.

Luo agrees that cutting back on bad news is a good thing and also recommends engaging with it more mindfully. “Be more aware of how much you can handle, and don’t let yourself be bombarded,” he says. “This way, you’re still in touch with what’s happening in the world, but you’re mindful of when you need to take a break from it all.” If you find yourself trapped in a doom-scrolling loop or feel yourself becoming more irritable, cynical or stressed while watching the news, that’s probably a good point at which to pause, he says.

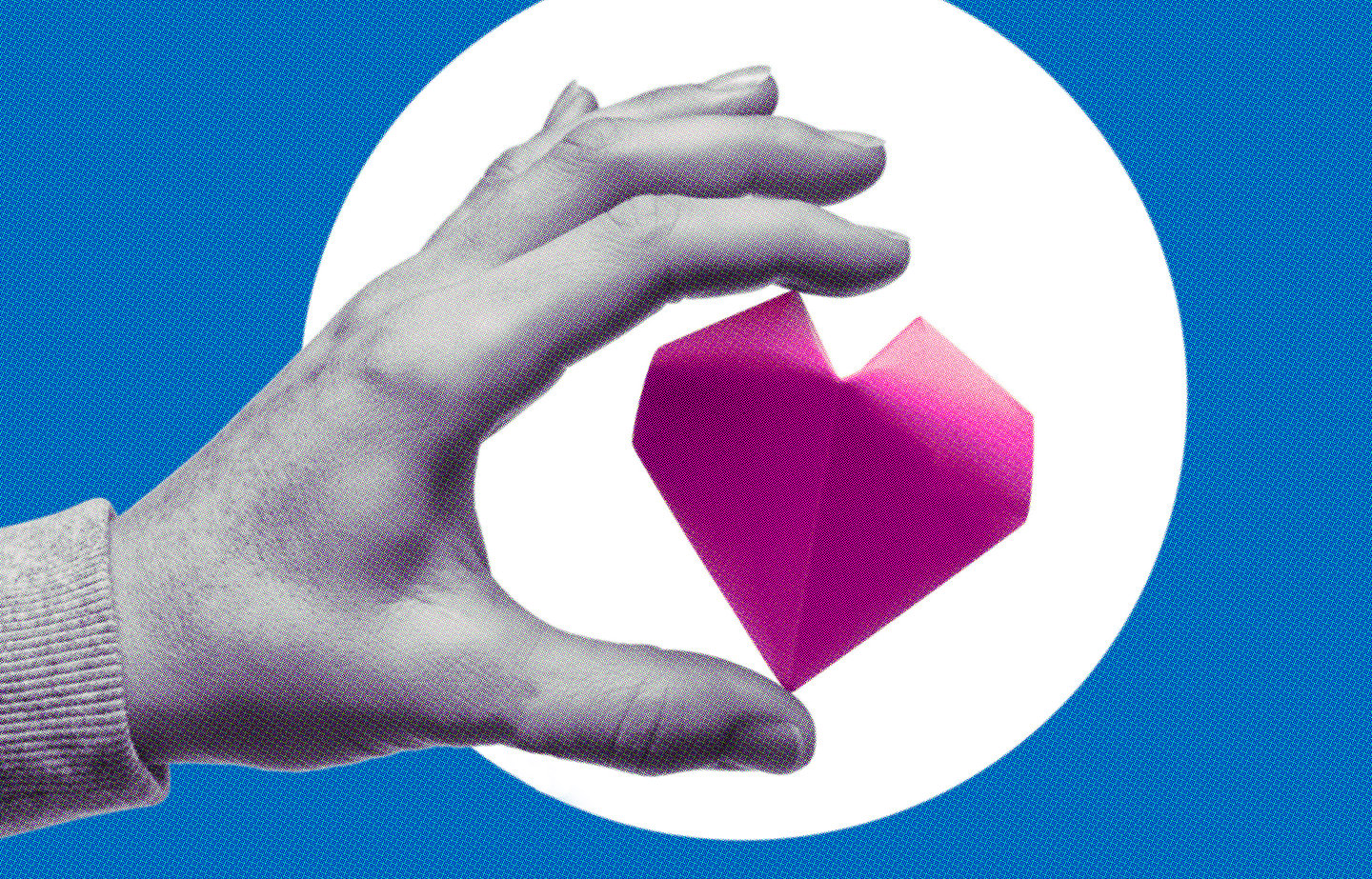

But although self-preservation is important, so is ensuring that our capacity for compassion remains intact. “When we’re facing crises at multiple levels, it’s even more important that we hang in there and offer empathy to others,” Luo says. “A lot of researchers have demonstrated that when people help others, they feel happier. If we help people or contribute to the things that we care about, we live a more fulfilling life.”

Lorem tore v

eri tatis et quasi archi te cto be.

Determined to fix the news, Lila launched Goodable – which he describes as “the Whole Foods of news” – offering positive, healthy content to balance out all the “fast food” (a.k.a. bad news). In 2020, he began posting good-news stories from around the world on social media, and, before long, Goodable had blossomed into a newsletter, an app, Goodable TV and, most recently, Goodable audio, reaching a combined audience of more than 100 million people a month – and counting.

“We need to make good news as pervasive as bad news so that people have a choice,” he says. “And there’s tremendous potential in reshaping how we think about the news – and using it as a tool to make the world better.”

Goodable stories range from good-news alerts (like when the European Commission set limits for underwater noise pollution to protect marine life) to posts championing people who are making a difference (like 12-year-old Madison Checketts from Eagle Mountain, Utah, who designed an edible water bottle after being dismayed by the proliferation of plastic bottles on beaches). There are also stories that celebrate good deeds (Canadian firefighters rescuing a fawn from a frozen lake) or that offer little moments of levity (what communities in Minnesota name their snowploughs: Edward Blizzardhands, The Big Leplowski, Ctrl Salt Delete).

News is so much more than just information, Lila says. It affects how you feel and has the power to change the trajectory of your day. “We don’t tell you all the bad news in the world, but we are tuned into the big stories so that we can find good things happening within them.” If there’s a shooting in the United States, instead of a headline that reads “Breaking news: Gunman storms into school, leaves 10 people dead,” a Goodable headline might read “Breaking news: Meet the janitor who saved a classroom full of children.”

When something terrible happens – a shooting, a fire, an accident on the street – Lila looks for the heroes who helped. In the heart-breaking aftermath of the earthquake in Turkey and Syria, Goodable ran a Twitter thread highlighting just some of the people who risked their lives to save others, from firefighters and volunteers to a seven-year-old girl who protected her little brother while they were trapped in the rubble. “I believe the world would be fundamentally better if every time a tragedy occurred, you could look at the news and see how many people helped.”

– MUHAMMAD LILA, GOODABLE

“We need to make good news as pervasive as bad

news so that people have a choice.”

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur autventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explic abo lorem ipsemu.

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia volu.

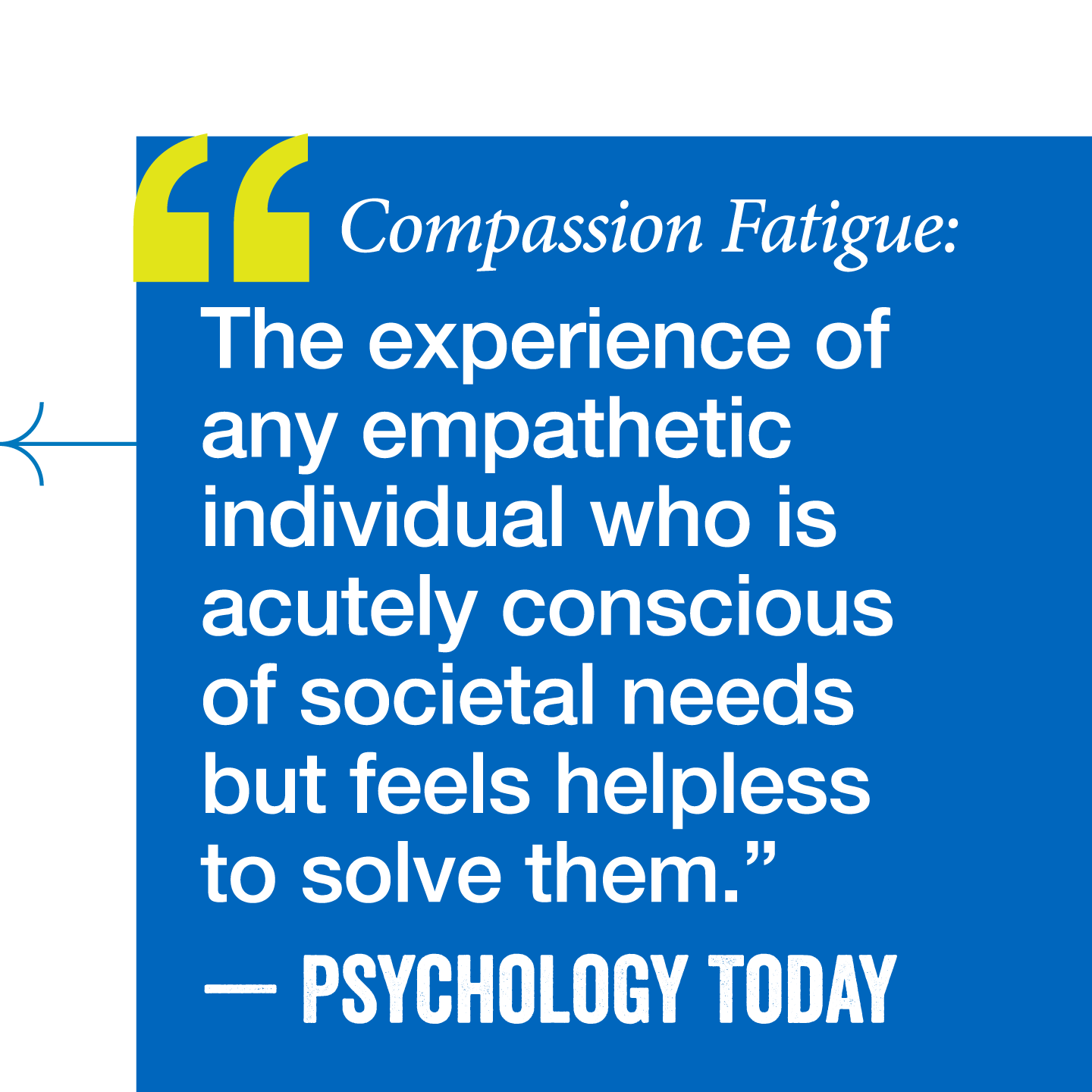

Luo has seen several “fatigues” afflicting his patients of late. One is compassion fatigue, which is defined by Psychology Today as “the experience of any empathetic individual who is acutely conscious of societal needs but feels helpless to solve them.” It’s a term often applied to people working in helping professions, such as doctors and nurses.

“The high demand on health care workers since the beginning of the pandemic has led to a burnout of compassion,” Luo says. “Many feel that they just don’t have enough empathy for their work anymore.” (In a 2022 study of nurses in Finland, researchers describe their compassion fatigue as “bruises in the soul.”)

Another type of tiredness that’s, ironically, making the news is “news fatigue.” Reuters’ 2022 Digital News Report found that people are so tired of the bad news beaming in from all over the globe that they’re actively avoiding it. (Of the 93,000 people surveyed, 36% said that tuning into the news lowers their mood, while 38% said they try to block it out altogether.)

Even journalists have had enough. In a September 2022 edition of Amplify, a weekly newsletter highlighting the insights of women at The Globe and Mail, design editor Lauren Heintzman examines her own news burnout and the daily exhaustion that comes with deciding which “haunting and relentless” images of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine to run on the front page. “The pressure of picking the right image to capture an entire country’s distress is incredibly daunting,” she writes. “And the guilt of doing so while safe and secure in my home can be overwhelming.”

Heintzman begins the piece with three words: “I am exhausted.” And later writes: “How can I balance compassion for others with compassion for myself? I keep coming back to this thought: You’re not checking out because you don’t care; you’re checking out because you have cared deeply for so long.”

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantiuitatis et ae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia volenim ipsam ae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia vol quia voluptas sit aspernatur autventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo lorem ipsemu.

Lorem tore v

eri tatis et quasi archi te cto be.

Caption 03:

Lorem tore v

eri tatis et quasi archi te cto be.

Caption 02:

Lorem tore v

eri tatis et quasi archi te cto be.

Caption 01:

Lorem tore v

eri tatis et quasi archi te cto be.

Every day, the headlines deliver another global gut punch. Take the recent news that the earth is actually dimming due to climate change. Of course it is.

It not only looks less shiny from space (warming oceans are leading to reduced cloud cover, muting its sun-mirroring effect) but it is also, quite literally, on fire. Or flooding. Or being levelled by catastrophic storms/tornadoes/hurricanes/earthquakes, depending on where you live. Meanwhile, in many countries, democracies are fracturing. Women’s rights are eroding. Devastating armed conflicts are grinding endlessly on. People are going hungry. Children are dying.

It’s getting harder and harder to face each new calamity with anything but a sense of sad resignation. A collective fatigue is setting in – and it’s not the kind you can fix with a good night’s sleep. Worse, this heavy, all-encompassing blanket of exhaustion is making us turn away from the news, shut down our emotions and seek solace in whatever’s trending on Netflix.

That may work just fine in the short term, but it’s not much of a solution, says Dr. Houyuan Luo, a clinical psychologist in Toronto who is increasingly seeing this fatigue in his patients – and experiencing it himself. “When we’re bombarded with negative news for too long, our automatic reaction is to run away and avoid it,” he says. “But people feel stressed because they care about these issues, and not paying attention to the things we care about isn’t consistent with our values. In the end, it won’t make us feel better.”

Fortunately, there are things that will. And it begins with understanding why so many of us are feeling overwhelmed, helpless and, sometimes, just too tired to care.

Words: Sydney Loney

Design: Rose Pereira

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut.

Yes, the world is in crisis (again). The daily news cycle is relentless – and emotionally draining. But here’s why the news isn’t all bad – and why it’s more important than ever to hang on to your capacity for compassion.

Finding the Good:

How to Fight

Compassion Fatigue

Why everyone is talking about being tired

How to handle the news

“If we help people or contribute to the things that

we care about, we live a more fulfilling life.”

The difference that doing good makes

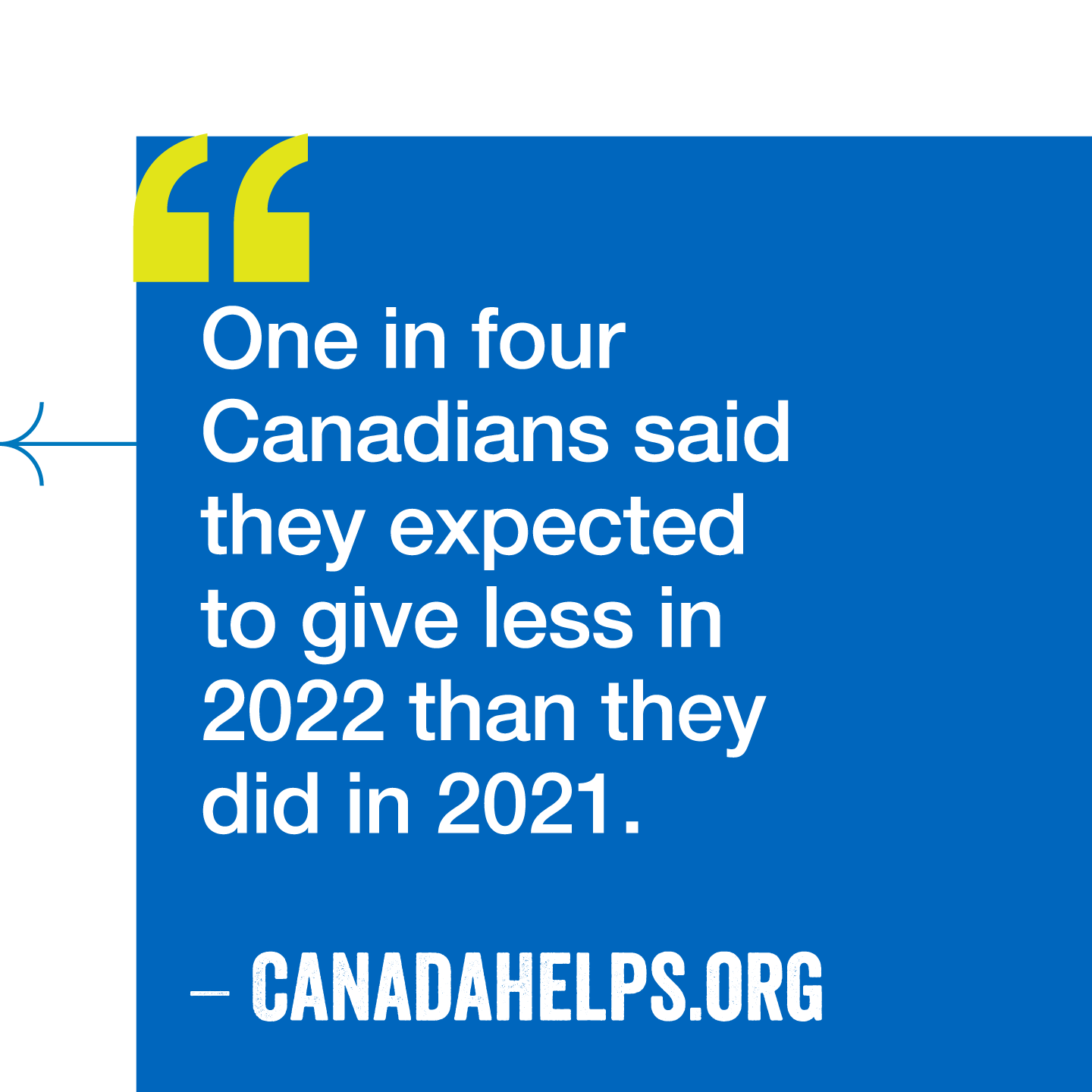

One fallout from news and compassion fatigue is that fewer people are helping others at a time when many people need more support than ever. (According to a recent report from CanadaHelps, one in four Canadians said they expected to give less in 2022 than they did in 2021 and rates of giving dropped overall from 24.6% in 2006 to 19% in 2019.) There is also a growing backlash to giving.

When Plan International Canada launched a social media campaign to draw attention to the global hunger crisis, not all the comments were positive: “Seems I could have read that headline many times in the last five decades. When does that bottomless pit end?” and “No more funds for other countries until we get our own house in order” and “This is really hard, because we can’t save everyone. It’s not our pain to take on.”

Omar Sabry, a policy and advocacy advisor for Plan International Canada, gets it. “It can be overwhelming when there are so many negative things happening in the world, and people often feel powerless to do anything about it,” he says. All of this has given rise to another form of fatigue: donor fatigue.

Sabry says that we need to fight these feelings. An unwavering belief that injustice is unacceptable is what continues to fuel his passion, even in the face of an unrelenting daily news cycle. And that includes injustice in Canada as well as elsewhere in the world; we have the capacity to address both, not one at the expense of the other, he says. “We’re all human beings, and we have an obligation to one another – to be in solidarity and to fight for one another’s rights. Just because there are multiple crises occurring at once doesn’t mean that we can lose hope, because if we lose hope, then what’s the point?”

“We’re all human beings, and we have an

obligation to one another – to be in solidarity

and to fight for one another’s rights.”

– OMAR SABRY, PLAN INTERNATIONAL CANADA

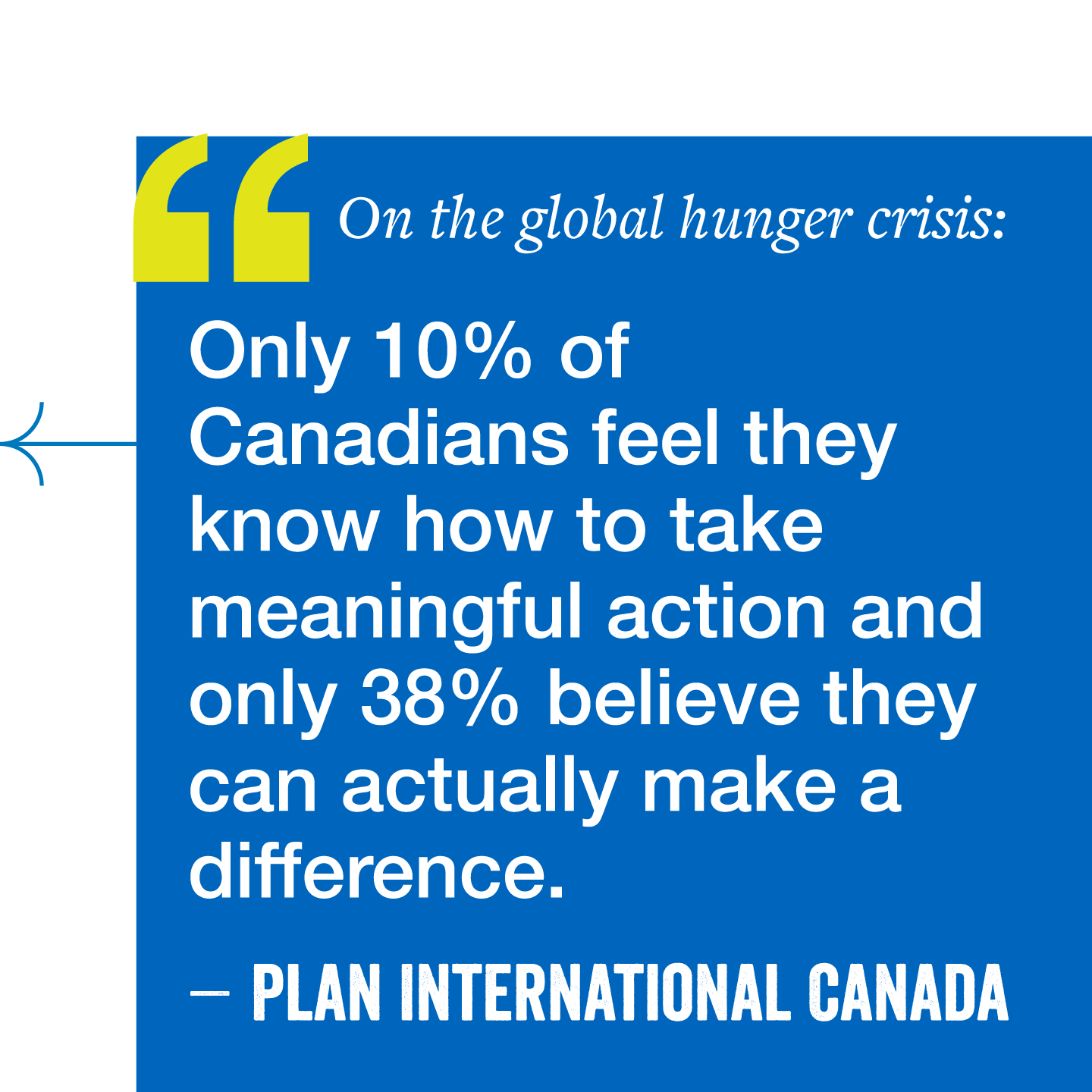

Holding on to hope – and knowing that no matter what you do, it does make a difference – is key. Plan International Canada conducted a survey related to the global hunger crisis and found that only 10% of Canadians feel they know how to take meaningful action and only 38% believe they can actually make a difference.

But, Sabry says, there is a lot you can do – whether it’s calling on government decision makers to address big issues or talking to people in your life to raise awareness about those issues. Luo says that too often people think they need to make a huge gesture when, really, it’s better to contribute within the scope of what’s possible for you in the moment. “We can volunteer, we can donate, we can contribute to our communities, we can do little things that still make the world a better place,” he says.

When you help other people, only good comes out of it, Lila adds. One of the Goodable stories that resonates most for him is about a professor who knew that many of her students relied on campus assistance for food. At the beginning of the pandemic, when many lost their jobs, she emailed her class and offered to make, and deliver, Thanksgiving dinners. “We came across a copy of the email, and we made it go viral,” Lila says. “Then we thought, ‘What if the rest of the world surprised her by doing something good in return?’”

Lila’s team asked followers whether they wanted to be part of the first Goodable project. “We got one reply every minute from people all around the world. It was the most wholesome thing I’d ever seen on social media. People were messaging, ‘Tell me what I can do.’”

The Goodable team decided to try to pay for the professor’s groceries for a year. In no time at all, they had raised thousands of dollars. But the best part, Lila says, is that when they told the professor that people from all over the globe wanted to thank her for her act of kindness, she insisted the money be given to the campus food-assistance program instead. “One person’s good deed ended up having an impact on hundreds of lives,” Lila says. “It shows that there’s a massive amount of goodwill out there for people who are willing to do good things. It shows how goodness spreads.”

And, he says, it also shows how good-news stories can inspire action.

Maybe that’s the best way to approach negative news too. When we hear about something sad in the world, instead of seeing it as just one more thing we can’t handle hearing about, we see it as one more thing we can feel better doing something about. “Yes, bad things are happening,” Lila says. “But the world is a beautiful place where amazing things are also happening every day. We can’t give up.”

And action might just be the perfect antidote to the fatigue we’re fighting.

tags

How finding the good can help

Bad things have always happened in the world, but there has always been a bright side to look on (otherwise, the cliché wouldn’t exist). There are studies that suggest that positive thinking and tapping into what you feel grateful for can bring you some comfort. A little self-care (even if you find the term “self-care” mildly irritating) may help too.

Heintzman began addressing her news burnout by turning to fiction, watching Euphoria in the tub, propagating plants and contributing resources to those in need. “While it can feel selfish to look away from all the hurt in the world, I also understand that I can care more fully if I pay attention to myself,” she writes. “‘Put on your own oxygen mask first,’ ‘you can’t pour from an empty cup’ and all that.”

You can also pretend you’re in a Marvel film and fight the bad by channelling the good. That’s what former CNN war correspondent Muhammad Lila did when, on a flight home from reporting on yet another armed conflict, he began wondering why he was only sent off to cover terror attacks, earthquakes, plane crashes, civil wars and assassinations. “I wanted to know, ‘Why is it that we’re only focusing on the bad things happening in the world?’”

THINK PIECE

“Journalists can include more solutions-based

stories that capture the possibility of change.

Avenues for action can be offered to readers to

counteract paralysis of tragedy.”

– REBECCA ROZELLE-STONE, PHILOSPHY PROFESSOR

Gifts of Hope

Give to where the need is greatest

SHOP NOW

Plan International Gifts of Hope make fighting fatigue (and spreading goodness) easy:

SHOP NOW

Fund a

food basket

Help refugee

children

SHOP NOW

SHOP NOW

Cash assistance

in crisis

Plan International found out that the majority of households in the Pujehan district of Sierra Leone couldn’t afford a radio, and when they do have one, girls don’t have access to it.

So, in partnership with Lifeline Energy, a non-profit social enterprise that designs, manufactures and distributes solar-powered radios across the world, Plan International procured 25,000 solar radio sets for girls. Fifteen-year-old Jeneba was one of the first to receive a set.

Good News from Plan International Canada

For girls caught up in the Rohingya crisis, life has been turned upside down. Having fled persecution in Myanmar, they now live in one of the largest refugee camps in the world in Bangladesh. Surrounded by nearly a million strangers, they have all had to adapt to life in an unfamiliar environment.

For adolescent girls in particular, this has been especially hard. With their families fearful for their safety in the camps, girls are often confined to their shelters making the friendships they form particularly important in building their resilience and helping them keep their hopes and dreams alive.

When Tejitu was 14, she overheard her family talking about a marriage proposal they’d received from a man in his 20s. She could tell they were keen to say yes.

In rural Amhara where she lives, 75% of girls are married before the age of 18, with many married off as young as 12. Tejitu was determined to stop her marriage from happening, so she called on her teachers and friends from the school peer to peer group to help her. Having all received training from the Girls Advocacy Alliance, they decided to report the case to the local anti-child marriage taskforce, which was formed by Plan International in 2016.

Within a year of opening, 11-year-old Thuem’s school in the indigenous Khmu community in Laos already had insufficient space for all its 400 students.

Recognizing that the needs of the schoolchildren and villagers were not being met, Plan International worked closely with government staff and authorities discuss the construction of a new permanent school building. Much to the excitement of the children, it also has electricity for lights and fans.

“I am very happy with new building and its facilities. Our school is clean and I feel safer studying there,” says Thuem. “We love our new school and it motivates us to go to school earlier.”

Smiling children outside one of the 30 Early Childhood Care Centres Plan International helped open in the Kibaha District in Tanzania. These centres

are places help teach children through play and support their physical and emotional development.

Finding the Good:

How to Fight

Compassion Fatigue

– DR. HOUYUAN LUO, CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST

back

to top

Words: Sydney Loney

Design: Rose Pereira

Give to where the need is greatest

Food basket

SHOP NOW

Food basket

SHOP NOW

Help refugee children

SHOP NOW

SHOP NOW