Donate

When food is in short supply, everyone suffers. But girls and women endure additional traumas and challenges because of their gender.

“Food insecurity is worsened by complex gender norms,” explains Saadya Hamdani, Director of Gender Equality and Inclusion at Plan International Canada. “Because of their age and gender, girls and women are often the most at risk for abuse and exploitation.”

In a new report, Beyond Hunger: The Gendered Impacts of the Global Hunger Crisis, Plan International surveyed, interviewed and held focus groups with more than 7,000 respondents between November 2021 and September 2022 in the eight countries most affected by the hunger crisis (Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, South Sudan, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Haiti).

Despite clear evidence that gender, in combination with age, (dis)ability and other factors, fundamentally shapes individuals’ vulnerability to and experiences of food insecurity, this is often overlooked in humanitarian responses to food crises. Moreover, responses frequently neglect the specific needs, risks and burdens faced by girls and women.

This report presents new evidence on the gendered impacts of the global hunger crisis and recommendations to address the specific needs of girls and women so that progress on gender equality isn’t undone.

Read the Report

Beyond Hunger:

the gendered impact

of the global hunger crisis

Donate

Five Reasons

Why Girls Suffer the Most When Food Is Scarce

When food is scarce, girls and women eat least and last, and that’s not all. Here are five key challenges they face.

Hunger Crisis

Girls get their lunch through a school feeding program run by Plan International in Kilifi county in Kenya.

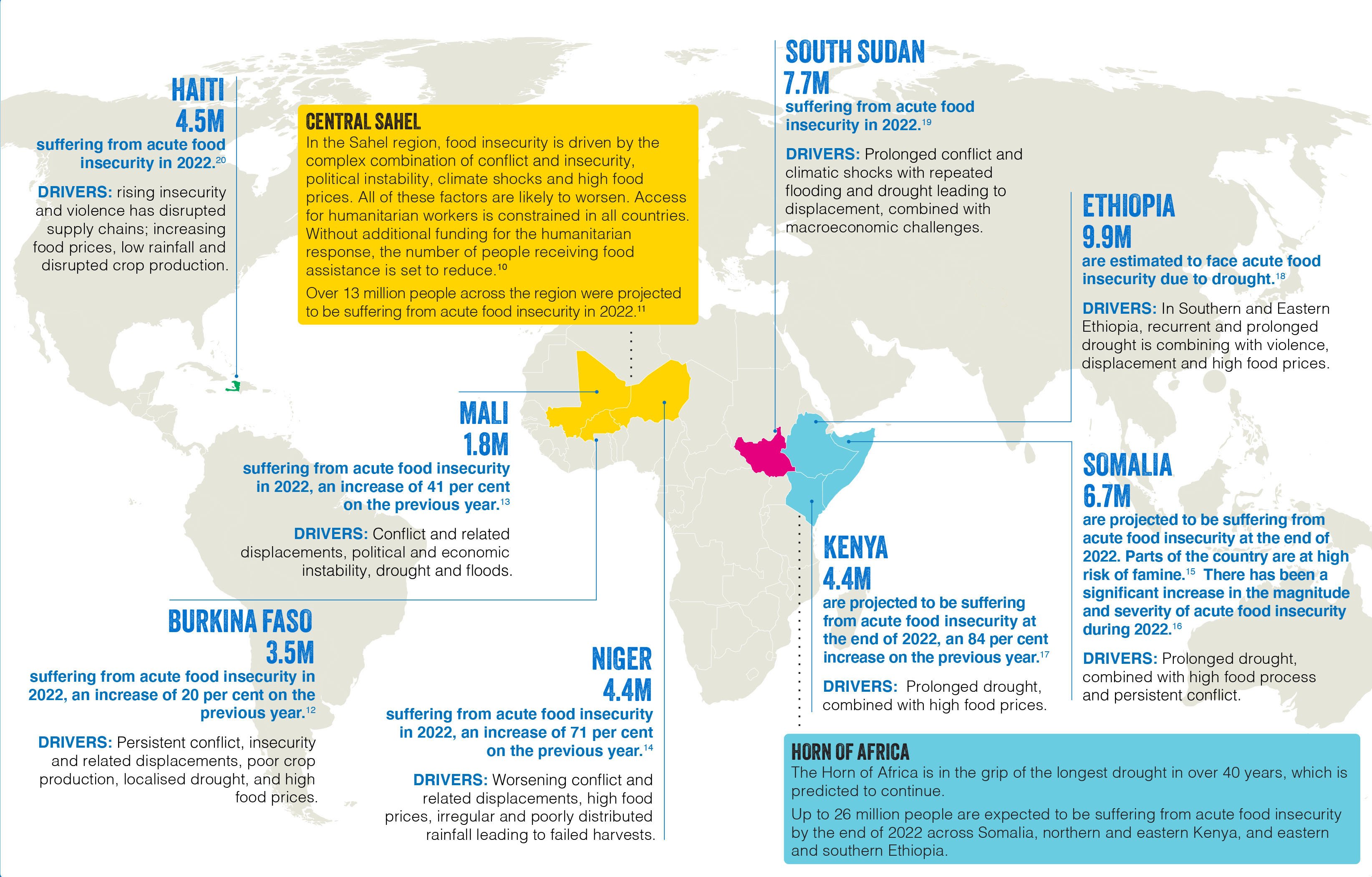

The worst global hunger crisis in decades is happening right now. It’s estimated that up to 828 million people do not have enough food to eat and 49 million people are facing emergency levels of hunger.

A number of factors are driving food insecurity, including conflict and instability, high food prices and climate shocks that destroy food crops and livestock and force displacement.

But not everyone is experiencing this crisis in the same way.

Available data suggests that in 2021,126.3 million more women than men were food insecure, and that gap is growing. And that’s not the full picture.

Most of the data that is collected focuses on adults and older adolescents. It’s been estimated that if children were to be included, there could be as many as 150 million more girls and women globally who are food insecure compared to boys and men.

Plan International’s Beyond Hunger report notes there is ample evidence that gender plays an important role in shaping children’s and adolescents’ experiences of food insecurity, including their protection and well-being, just as it does for adults.

Hunger Crisis Update

1. Access to food is different for them than it is for boys and men.

2. Less access to food leads to an increased risk of gender-based violence, abuse and exploitation.

3. Girls are married off early to reduce the financial burden on families.

4. Education isn’t a priority for girls.

5. Menstrual products, contraceptives and sexual and reproductive health care services become increasingly inaccessible.

Here are five ways hunger affects adolescent girls and women:

1. Girls and women don’t have the same access to food.

If there’s a shortage of food at home, girls and women often eat less and eat after the boys and men. In some countries, there is evidence that gender discrimination related to food starts when children are babies. In Haiti, for example, it was reported that male babies are breastfed longer to make them physically stronger.

The report’s authors conducted focus groups with boys and young men in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger to explore whether gender determines or influences who has access to food. They learned that while gender discrimination exists, it’s not a universally held view and doesn’t go unchallenged.

In Burkina Faso, for example, while around a third of focus-group participants agreed that boys and men should sometimes or always be prioritized for meals, the majority agreed that this shouldn’t be the case. Additionally, almost half of young men in focus groups in Burkina Faso reported that they always challenge sexism.

2. Less access to food leads to an increased risk of gender-based violence, abuse and exploitation.

Tension, anxiety and stress build up in a home when a family is hungry. This can lead to violent outbursts, which are most often directed at girls and women.

“The woman always asks for food, and the husband, for lack of means, scolds or insults her, and they can beat each other up, which sometimes leads to the woman running away from home,” one participant from Niger reported.

Workloads also shift when families need food to survive. Girls and women spend more time collecting food, water and firewood. They often walk long distances in potentially dangerous remote areas or wait in long lines at food-distribution sites, where they are harassed.

“Travelling long distances at nighttime is very risky for us,” says one participant in a discussion group led by Plan International in Ethiopia. “Younger girls and women are exposed to sexual violence… and they are endangered by wild animals like hyenas. However, mostly we prefer to go to the water sources at night just to avoid the competition.”

In order to find food, girls and women sometimes make impossibly difficult choices to survive.

“Some young women engage in sexual relationships with the security guards who are assigned to protect the shelter,” shared one of the local government officials in Ethiopia who was interviewed for the report. “The women stay in these relationships because the guards promise to support them and marry them in the future; however, they leave without a trace after impregnating them.”

3. Girls are married off early to reduce the burden on families.

Survey participants from Mali, Niger and Ethiopia specifically mentioned that child, early and forced marriage has increased during the current food crisis. In some of the affected areas in Ethiopia, for example, child marriage cases have reportedly increased by 51% in a year. In South Sudan, a forced engagement, or “booking” can start when a girl is two years old because dowry payments are considered an important source of income.

Some families also resort to child marriage to reduce financial burdens and to have one less family member to feed. Yet in some cases, amid limited options, girls have been reported to initiate early marriages themselves to increase their own access to food.

Girls who marry before the age of 18 are more likely to experience intimate partner violence, and they often drop out of school. The other concern is that early marriage often leads to early and frequent pregnancies, with the associated risks of complications and maternal and infant death. In Niger, for example, 36% of adolescent girls aged 15 to 19 are pregnant or have already given birth.

4. Education isn’t a priority for girls.

When food and water are scarce, children – most often girls – miss school to help find what they can to nourish their families. While the food crisis has reduced access to education for both boys and girls, the research gathered from the report showed that girls’ education has been disproportionately deprioritized.

Almost half of boys and men who participated in focus groups in Burkina Faso thought that girls’ education should be put on hold some or all the time because of the hunger crisis. There was some evidence that girls also deprioritize their education during a hunger crisis. None of the girls and young women in focus groups in Mali, for example, felt that education was important. In Niger and Haiti, other focus groups found that both girls and boys are losing interest in their studies.

And for those who do stay in school, being hungry affects their ability to learn. If children don’t get proper nutrition from an early age, their brain development can be stunted, leading to learning difficulties. Children experiencing hunger also often struggle to focus in class and aren’t easily able to build life skills. “When you don’t have a full belly, you can’t study,” said a girl from a focus group in Burkina Faso.

When children drop out of school early, the immediate and longer-term impacts are significant and differ by gender. School dropout, child labour and early marriage are closely intertwined. When children lose the protection of being in school, their exposure to other risks and violations increases. For girls, child marriage is both a cause and a consequence of dropping out of school.

5. Menstrual products, contraceptives and sexual and reproductive health services become increasingly inaccessible.

When families can’t afford to buy food, they often sacrifice other essential items, like menstrual products and contraceptives. This jeopardizes girls’ health and puts them at risk of early pregnancy. In Kenya, for example, 40% of girls and women of reproductive age surveyed do not have their menstrual health needs met.

In many countries, girls’ and women’s sexual and reproductive health needs were already underserved and their need for these services has increased due to the sexual violence and sexual exploitation that has led to unplanned pregnancies and STIs.

“Yesterday I went to the health centre,” said a young pregnant woman in Ethiopia. “I [had] to travel a long distance by foot. I felt very tired and sick when I got home.”

During interviews with community leaders in Ethiopia, it was reported that this year, in the area studied, 28 newborn infants were found left on the street as mothers were unable to look after them.

While in most cases, access to health care, including sexual and reproductive health services, was reported to be poor, Somalia was an anomaly: 82% of survey respondents in the area studied said they had access to health services. Mental health care, however, remains a gap – only 9% of 100 of the respondents in Somalia reported having access to psychosocial support services, despite the level of physical, sexual and emotional violence experienced by the affected population.

More than 6,000 displaced people fleeing emergencies reside in the small town of Koupela in Burkina Faso. The majority are women and children who arrive with nothing. Their biggest needs are food, water and shelter.

Inflation, soaring food and fuel costs and gang violence have caused widespread food insecurity for millions of people in Haiti. Loveca, 8, lives with her cousin Mirlande, 23. Because of Mirlande’s poor health, Loveca often has to collect water for her family.

A woman collects a food kit in Niger, where they are experiencing the worst hunger crisis seen in decades. Increasingly erratic rainfall and longer dry seasons mean that many parts of the country have not had a good harvest for years.

Plan International works with communities facing hunger to promote gender equality, distribute food and essentials and help families develop sustainable agricultural practices. You can help us save lives and protect the rights of millions of children and girls by:

1. Supporting the $18 School Essentials for

One Child Gift of Hope

In addition to textbooks and pencils, this gift helps fund school-meal programs. School meals provide a strong incentive for parents and caregivers to send their children to school and can reduce gender disparities in education outcomes.

2. Learning more about

the gendered impacts of hunger and how you can help fight hunger.

Help Fight Hunger

Help children caught in

the worst hunger crisis

our world has seen.

Read

A group of women wait for food distribution in South Sudan, where hunger and malnutrition rates and are soaring due to the lack of food brought on by the country’s worst drought in 40 years.

South Sudan is experiencing its worst drought in 40 years following the failure of four consecutive rainy seasons, causing severe food insecurity. Monica (front) is waiting in a distribution line to receive a package of food that should last for the next two months, which includes cereal, pulses, vegetable oil and salt.

How we’re helping communities fight hunger

What can we do?

1. We support school feeding programs to deliver healthy meals to children while they learn. (Amongst the countries included in this report, Plan International is implementing school meals programs in Kenya, Ethiopia and South Sudan. In 2022, Plan International Kenya reached over 22,500 children across four counties with a midday hot meal.)

2. We help protect girls and those most at risk from threats like violence and child marriage by strengthening community safety programs.

3. We help families secure agriculture and business training, tools and equipment.

4. We distribute emergency food, hygiene kits and cash vouchers to those most vulnerable to hunger.

Back

to list

Back

to list

Back

to list

Back

to list

Back

to list

GLOBAL HUNGER HOTSPOTS

When food is in short supply, everyone suffers. But girls and women endure additional traumas and challenges because of their gender.

“Food insecurity is worsened by complex gender norms,” explains Saadya Hamdani, Director of Gender Equality and Inclusion at Plan International Canada. “Because of their age and gender, girls and women are often the most at risk for abuse and exploitation.”

In a new report, Beyond Hunger: The Gendered Impacts of the Global Hunger Crisis, Plan International surveyed, interviewed and held focus groups with more than 7,000 respondents between November 2021 and September 2022 in the eight countries most affected by the hunger crisis (Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, South Sudan, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Haiti).

Despite clear evidence that gender, in combination with age, (dis)ability and other factors, fundamentally shapes individuals’ vulnerability to and experiences of food insecurity, this is often overlooked in humanitarian responses to food crises. Moreover, responses frequently neglect the specific needs, risks and burdens faced by girls and women.

This report presents new evidence on the gendered impacts of the global hunger crisis and recommendations to address the specific needs of girls and women so that progress on gender equality isn’t undone.

1. Girls and women don’t have the same access to food.

If there’s a shortage of food at home, girls and women often eat less and eat after the boys and men. In some countries, there is evidence that gender discrimination related to food starts when children are babies. In Haiti, for example, it was reported that male babies are breastfed longer to make them physically stronger.

The report’s authors conducted focus groups with boys and young men in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger to explore whether gender determines or influences who has access to food. They learned that while gender discrimination exists, it’s not a universally held view and doesn’t go unchallenged.

In Burkina Faso, for example, while around a third of focus-group participants agreed that boys and men should sometimes or always be prioritized for meals, a majority agreed that this shouldn’t be the case. Additionally, almost half of young men in focus groups in Burkina Faso reported that they always challenge sexism.

2. Less access to food leads to an increased risk of gender-based violence, abuse and exploitation.

Tension, anxiety and stress build up in a home when a family is hungry. This can lead to violent outbursts, which are most often directed at girls and women.

“The woman always asks for food, and the husband, for lack of means, scolds or insults her, and they can beat each other up, which sometimes leads to the woman running away from home,” one participant from Niger reported.

Workloads also shift when families need food to survive. Girls and women spend more time collecting food, water and firewood. They often walk long distances in potentially dangerous remote areas or wait in long lines at food-distribution sites, where they are harassed.

“Travelling long distances at nighttime is very risky for us,” says one participant in a discussion group led by Plan International in Ethiopia. “Younger girls and women are exposed to sexual violence … and they are endangered by wild animals like hyenas. However, mostly we prefer to go to the water sources at night just to avoid the competition.”

In order to find food, girls and women sometimes make impossibly difficult choices to survive.

“Some young women engage in sexual relationships with the security guards who are assigned to protect the shelter,” shared one of the local government officials in Ethiopia who was interviewed for the report. “The women stay in these relationships because the guards promise to support them and marry them in the future; however, they leave without a trace after impregnating them.”

3.Girls are married off early to reduce the burden on families.

Survey participants from Mali, Niger and Ethiopia specifically mentioned that child, early and forced marriage ) has increased during the current food crisis. In some of the affected areas in Ethiopia, for example, child marriage cases have reportedly increased by 51% in a year. In South Sudan – where forced engagement, or “booking,” can start when a girl is two years old – dowry payments are considered an important source of income.

Some families also resort to child marriageto reduce financial burdens and to have one less family member to feed. Yet in some cases, amid limited options, girls have been reported to initiate early marriages themselves to increase their own access to food.

Girls who marry before the age of 18 are more likely to experience intimate partner violence, and they often drop out of school. The other concern is that early marriage often leads to early and frequent pregnancies, with the associated risks of complications and maternal and infant death. In Niger, for example, 36% of adolescent girls aged 15 to 19 are pregnant or have already given birth.

4. Education isn’t a priority for girls.

When food and water are scarce, children – most often girls – miss school to help find what they can to nourish their families. While the food crisis has reduced access to education for both boys and girls, the research gathered from the report showed that girls’ education has been disproportionately deprioritized.

Almost half of boys and men who participated in focus groups in Burkina Faso thought that girls’ education should be put on hold some or all the time because of the hunger crisis. There was some evidence that girls also deprioritize their education during a hunger crisis. None of the girls and young women in focus groups in Mali, for example, felt that education was important. In Niger and Haiti, other focus groups found that both girls and boys are losing interest in their studies.

And for those who do stay in school, being hungry affects their ability to learn. If children don’t get proper nutrition from an early age, their brain development can be stunted, leading to and learning difficulties. Children experiencing hunger also often struggle to focus in class and aren’t easily able to build life skills. “When you don’t have a full belly, you can’t study,” said a girl from a focus group in Burkina Faso.

When children drop out of school early, the immediate and longer-term impacts are significant and differ by gender. School dropout, child labour and early marriage are closely intertwined. When children lose the protection of being in school, their exposure to other risks and violations increases. For girls, child marriage is both a cause and a consequence of dropping out of school.

5. Menstrual products, contraceptives and sexual and reproductive health services become increasingly inaccessible.

When families can’t afford to buy food, they often sacrifice other essential items, like menstrual products and contraceptives. This jeopardizes girls’ health and puts them at risk of early pregnancy. In Kenya, for example, 40% of girls and women of reproductive age surveyed do not have their menstrual health needs met.

In many countries, girls’ and women’s sexual and reproductive health needs were already underserved., their need for these services has increased due to the sexual violence and sexual exploitation that has led to unplanned pregnancies and STIs.

“Yesterday I went to the health centre,” said a young pregnant woman in Ethiopia. “I [had] to travel a long distance by foot. I felt very tired and sick when I got home.”

During interviews with community leaders in Ethiopia, it was reported that this year, in the area studied, 28 newborn infants were found left on the street as mothers were unable to look after them.

While in most cases, access to health care, including sexual and reproductive health services, was reported to be poor, Somalia was an anomaly: 82% of survey respondents in the area studied said they had access to health services. Mental health care, however, remains a gap – only 9% of 100 of the respondents in Somalia reported having access to psychosocial support services, despite the level of physical, sexual and emotional violence experienced by the affected population.

1. Girls and women don’t have the same access to food.

If there’s a shortage of food at home, girls and women often eat less and eat after the boys and men. In some countries, there is evidence that gender discrimination related to food starts when children are babies. In Haiti, for example, it was reported that male babies are breastfed longer to make them physically stronger.

The report’s authors conducted focus groups with boys and young men in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger to explore whether gender determines or influences who has access to food. They learned that while gender discrimination exists, it’s not a universally held view and doesn’t go unchallenged.

In Burkina Faso, for example, while around a third of focus-group participants agreed that boys and men should sometimes or always be prioritized for meals, a majority agreed that this shouldn’t be the case. Additionally, almost half of young men in focus groups in Burkina Faso reported that they always challenge sexism.

3.Girls are married off early to reduce the burden on families.

Survey participants from Mali, Niger and Ethiopia specifically mentioned that child, early and forced marriage has increased during the current food crisis. In some of the affected areas in Ethiopia, for example, child marriage cases have reportedly increased by 51% in a year. In South Sudan, forced engagement or “booking” can start when a girl is two years old because dowry payments are considered an important source of income.

Some families also resort to child marriage to reduce financial burdens and to have one less family member to feed. Yet in some cases, amid limited options, girls have been reported to initiate early marriages themselves to increase their own access to food.

Girls who marry before the age of 18 are more likely to experience intimate partner violence, and they often drop out of school. The other concern is that early marriage often leads to early and frequent pregnancies, with the associated risks of complications and maternal and infant death. In Niger, for example, 36% of adolescent girls aged 15 to 19 are pregnant or have already given birth.

4. Education isn’t a priority for girls.

When food and water are scarce, children – most often girls – miss school to help find what they can to nourish their families. While the food crisis has reduced access to education for both boys and girls, the research gathered from the report showed that girls’ education has been disproportionately deprioritized.

Almost half of boys and men who participated in focus groups in Burkina Faso thought that girls’ education should be put on hold some or all the time because of the hunger crisis. There was some evidence that girls also deprioritize their education during a hunger crisis. None of the girls and young women in focus groups in Mali, for example, felt that education was important. In Niger and Haiti, other focus groups found that both girls and boys are losing interest in their studies.

And for those who do stay in school, being hungry affects their ability to learn. If children don’t get proper nutrition from an early age, their brain development can be stunted, leading to and learning difficulties. Children experiencing hunger also often struggle to focus in class and aren’t easily able to build life skills. “When you don’t have a full belly, you can’t study,” said a girl from a focus group in Burkina Faso.

When children drop out of school early, the immediate and longer-term impacts are significant and differ by gender. School dropout, child labour and early marriage are closely intertwined. When children lose the protection of being in school, their exposure to other risks and violations increases. For girls, child marriage is both a cause and a consequence of dropping out of school.

Back

to list

Back

to list

Back

to list

Back

to list

Donate

Read the Report

Beyond Hunger:

the gendered impact

of the global hunger crisis

Learn More

It’s normal to feel stressed and helpless when you’re hit with negative news day after day. But learn why you should still care and what you can do.

Words: Plan International Staff

Design: Rose Pereira

Reading time: 14 minutes