When Nhial Deng looks back on his early childhood in Ethiopia, it was beautiful.

He lived a quiet life with his father. And when he wasn’t in school, he spent his time swimming in the Nile River and playing soccer with his friends in big, open fields.

“It was a beautiful childhood – a stable and normal childhood,” says the now 24-year-old Deng.

Then, in April 2010, everything changed.

Early one morning, Deng woke to the sound of gunshots.

Insurgent forces were descending onto his small town, and everyone had to flee.

Deng’s father gave him a paper bag stuffed with clothes and some water and shoved him out the door.

“I was so frightened,” he remembers. “I could hear people screaming outside, and my dad just said, ‘Get out, you have to get to a safe place.’”

He would not hear his father’s voice again for three years.

Deng was 11 years old.

watch

Plan International Canada’s Embedded Storytellers pilot project

read more

Nhial Deng grew up in Kenya in one of the largest refugee camps in the world. Today, he’s attending university in Canada and on a mission to empower youth voices.

Words by Linda Nguyen

Design by Rose Pereira

Reading time: 10 minutes

child refugee

• It was established in 1992 when large groups of refugees began arriving after the fall of the Ethiopian government and civil strife in Somalia.

• It is located in the northwest region of Kenya.

• Kakuma is the Swahili word for “nowhere.”

• In 2020, there were nearly 200,000 registered refugees and asylum seekers living in Kakuma; it’s estimated that that figure is now closer to 250,000.

• There are more than 19 nationalities living in the refugee camp, including those from Somalia, Ethiopia, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Uganda and Rwanda.

• More than 56% of the population is from South Sudan.

• It is one of the largest refugee camps in the world.

• In 2016, five refugees from the Kakuma Refugee camp competed in the Rio Olympic Games as part of the first-ever Olympic Refugee team.

Source: UNHCR: The UN Refugee Agency and UNICEF

Facts about Kakuma Refugee Camp

“Deng was able to use the internet to research some of the world’s best universities, including some in California and England he dreamed of one day attending.

He took free online courses and learned all he could about the United Nations, journalism and peacebuilding.”

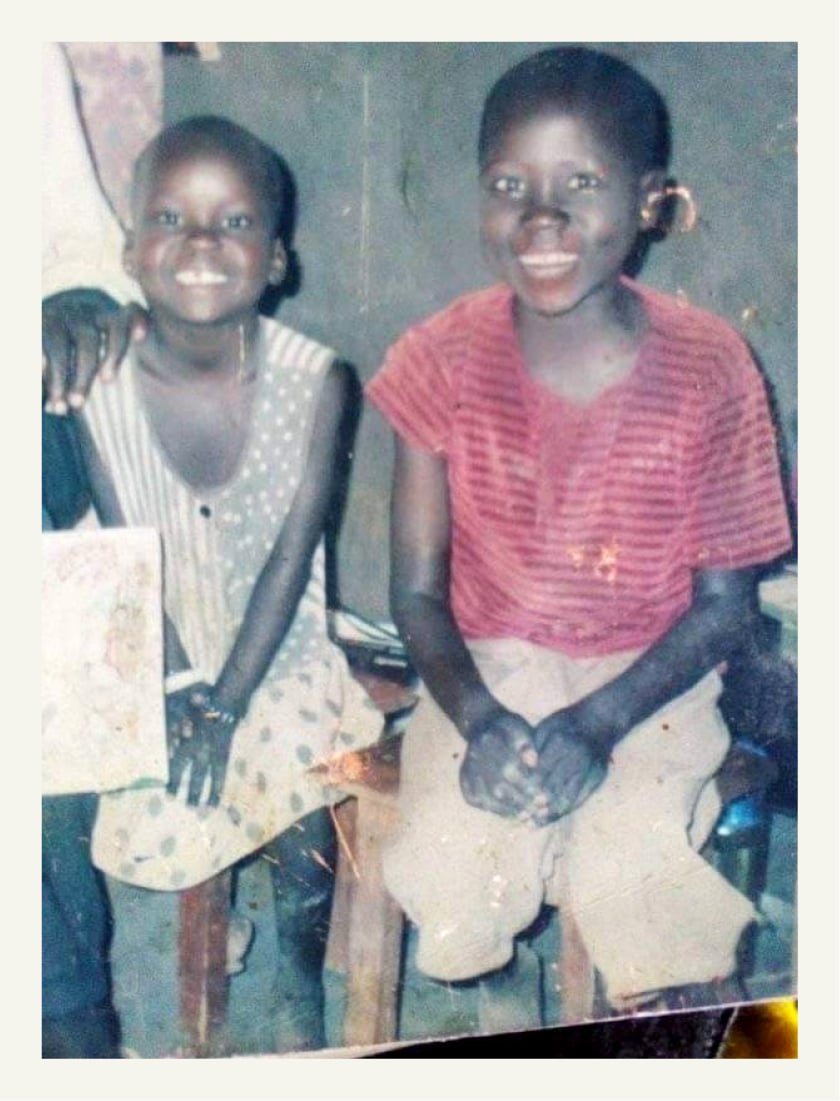

Nhial Deng, 8, and his younger sister Nyamal, 5, together in Ethiopia in 2007.

Like most men in the village, Deng’s father stayed behind.

This wasn’t a new experience for his father, who had to flee South Sudan twice in the 1960s and 1970s due to violence.

At the time, Deng and his father were living separately from his mother and younger siblings so Deng could attend a better school. He would only get to see his mother and six siblings for the first time again last December.

“This conflict came out of nowhere,” says Deng, a former summer intern in the Advocacy department at Plan International Canada and currently a student at Huron University College in London, Ont.

“In my mind, I had a life plan. I was going to finish primary school, and then I would go to high school and perform well and get a scholarship and study journalism at the university in Addis Ababa. After that, I would get a job at the BBC. That’s what I was working toward. It never crossed my mind – not for a single moment – that I would have to flee my bed and walk for days to get to a refugee camp.”

Arriving at one of the world’s largest refugee camps

That morning, Deng joined a group of 25 people – mostly women and children – from his village and began walking.

The group walked for two days before they were able to find a safe place to rest. Then, miraculously, they were able to board a truck for a short period before walking again.

Two weeks later, Deng arrived in Kenya at the Kakuma Refugee Camp and Kalobeyei Integrated Settlement, run by the UN Refugee Agency.

He didn’t have any official personal identification; all he had was an old school report card.

Little did he know, Kakuma would be his home for the next 11 years.

“Education is the tool you need for a better life”

Deng was assigned to live with a family he did not know, and after two months, he was allowed to start attending school. Despite the interruption, he was determined to follow his dreams.

“Education is the tool you need for a better life,” says Deng.

“That has always been emphasized to me. I had a dream I wanted to fulfill, and my dad believed that that dream was possible.”

The school, which is funded by the UN Refugee Agency in partnership with the Kenyan government, was mostly for refugee children from the Kakuma camp.

When Deng attended, there were 1,500 students.

In 2016, Deng’s high school received funding for computers with internet access. This addition changed his life and those of his peers.

Until then, all they had ever seen was extreme poverty. His neighbours, friends and new family were all refugees like him – people who had been ripped from their homes and forced to flee.

Deng says that everyone living at the camp – which has a population the size of Saskatoon – are restricted from working or ever leaving the camp without special permission.

Many people end up living and languishing at the camp for decades. They’re prevented from being able to start over in Kenya but are also unable to return to their home countries.

Yet despite this sense of helplessness, he fondly remembers being taught to dream big and dream often.

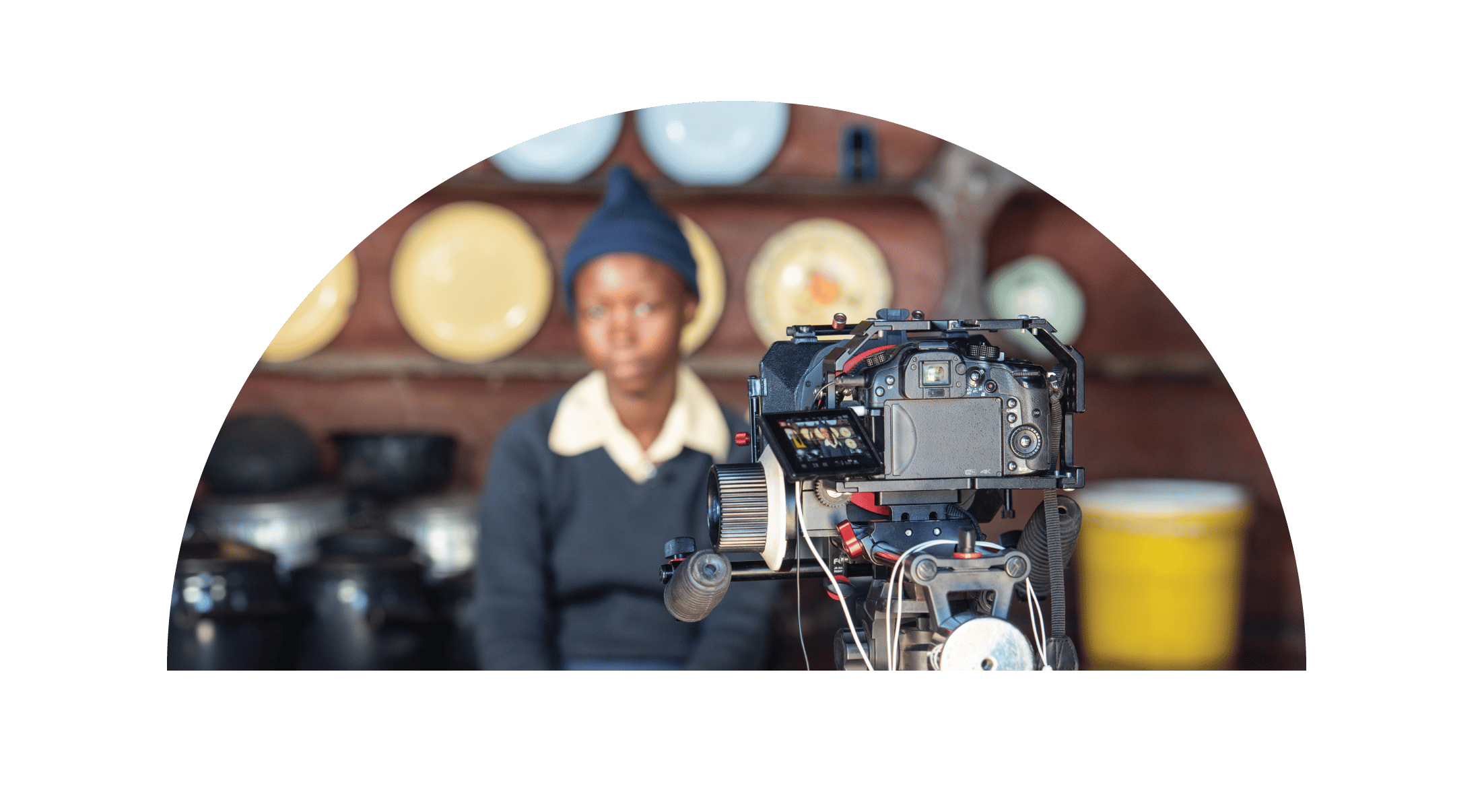

Nhial Deng (sitting on the right) being interviewed by a short film crew for the UN Human Rights campaign #StandUp4Migrants in 2021.

Access to the internet connected them to the world

Find out how you can help refugee children all around the world

Teaching others how to tell their own stories

At his high school, Deng also started a journalism club to put the power of storytelling back into the hands of the storytellers.

“I think storytelling is how people connect,” he says.

To date, the club has helped teach more than 250 refugee children how to write their own stories.

“They talk about their dreams. Some want to be pilots, some want to be teachers and some want to be presidents of their countries,” says Deng.

“They’re documenting why they fled their countries and their journeys back home as well as their lives at camp and school.”

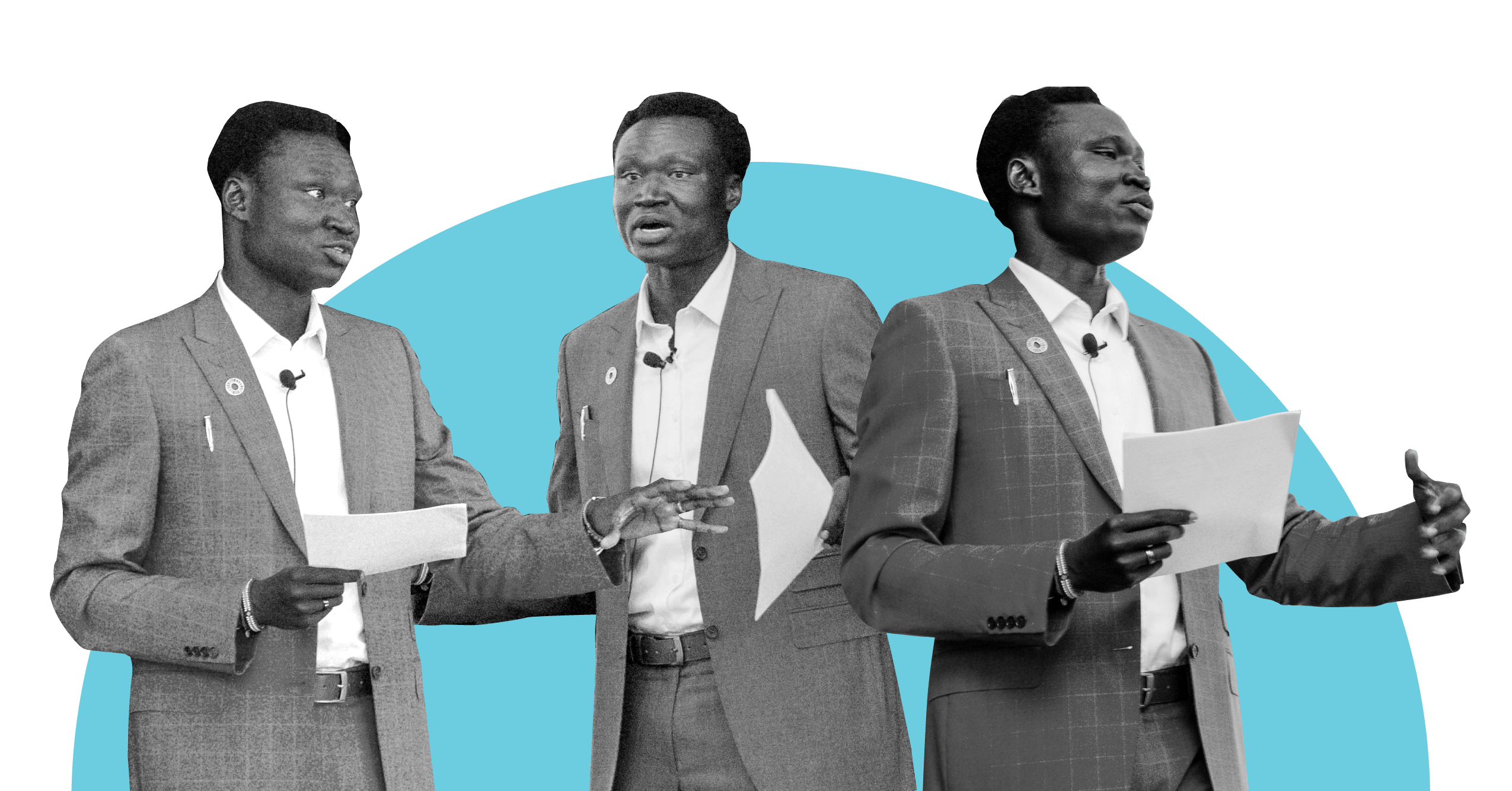

Nhial Deng, 24, gives a keynote speech to Plan International Canada staff last February in Toronto. He touched on his experience as a child refugee and the power of youth voices.

The power of youth voices

Empowering youth voices has long been Deng’s mission. Listening to other refugees like himself has been his heart’s work and a way for him to deal with his own traumatic childhood.

Although he no longer dreams of becoming a professional TV broadcaster, Deng is still intent on amplifying the voices of young people.

“Meaningful youth engagement is about not just creating a seat at the table but also ensuring that young people have access to the tools and resources they need to effectively engage in the discussions,” he says.

“Investing in youth leadership is not a favour to us, the young people. It is good for the world. It is good for all of us. And it is good for the work we do.”

When Deng left to come to Canada for university in 2021, Kakuma’s population was nearly 200,000.

He remembers his first impressions of Canada was that it really is that cold here and that Western society is much more individualistic than what he’s used to.

What’s next for Deng once he graduates from Huron University College?

He still wants to go to graduate school in California or England and hopes to one day build life for himself in Kenya.

Deng is still dreaming big.

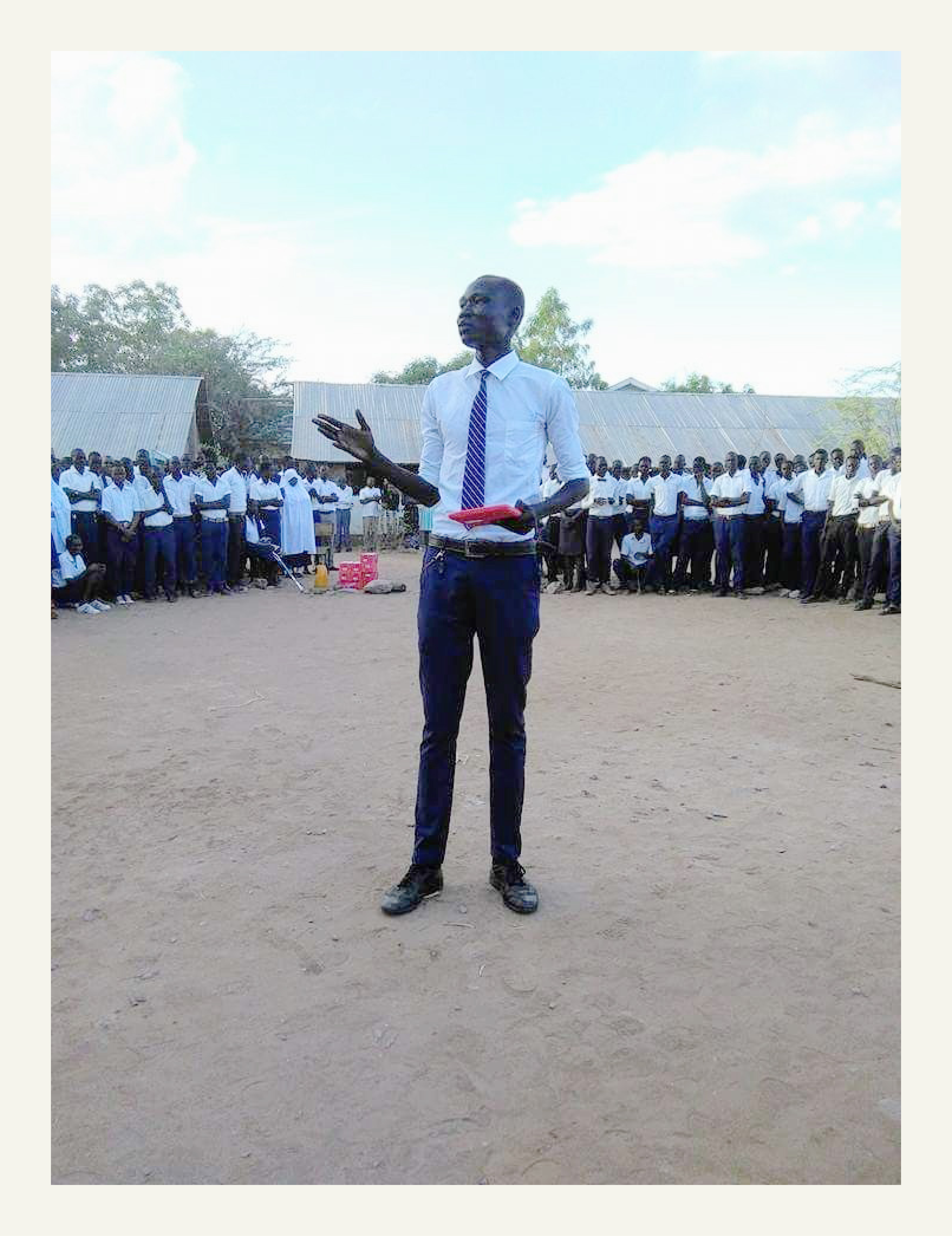

Nhial Deng gives a speech during the morning assembly at his high school in Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya in 2017.

He recalls a time when a former South Sudanese refugee visited the camp and spoke to the children about being a trained pilot in Australia. This one person’s powerful story showed Deng and his friends that there were no impossible dreams.

Being able to go online also opened up the world to Deng and his fellow peers.

Deng was able to use the internet to research some of the world’s best universities, including some in California and England he dreamed of one day attending. He took free online courses and learned all he could about the United Nations, journalism and peacebuilding.

“It gave me a global perspective of the world,” he says.

Armed with that new knowledge, Deng became active on social media, building his following while still living at the camp. His unique voice helped him connect with people all around the world, and soon, he started being invited to speak at conferences about his experience as a child refugee.

and how it is changing the way we tell stories about our work.

Watch some of our

most hopeful videos

of 2022

Want more inspiration?