Gender inequality

sits at the heart of

global health issues

Words: Mandy Sherman

Design: Rose Pereira

Reading time: tk

Mavis provides prenatal counseling to a mother visiting her clinic

Ambulances and health equipment only go so far to prevent maternal mortality

Inequality creates the conditions; women’s health pays the price

Change for women and girls needs men and boys on board

From Haiti, Senegal, Bangladesh, Nigeria and Ghana - the results are in!

Getting to a health clinic is only half the battle

For girls’ health, the changes are starting to show

Power and permission play a role in women’s health

If Fabien could go back in time and do things over with the knowledge he has now, he would have a little brother.

When Fabien’s mother was pregnant with his should-have-been baby brother, she contracted typhoid and malaria. These two diseases are preventable and treatable with access to the right information and sufficient health care. But in their remote village in rural Haiti, Fabien’s mother had neither. She survived but delivered her baby premature and stillborn.

“The doctor told us he could not save them both,” Fabien says.

In Fabien’s village, most families don’t have access to basic health care and health information. This includes the kind of information that could have saved Fabien’s infant brother, like how to spot early warning signs during pregnancy.

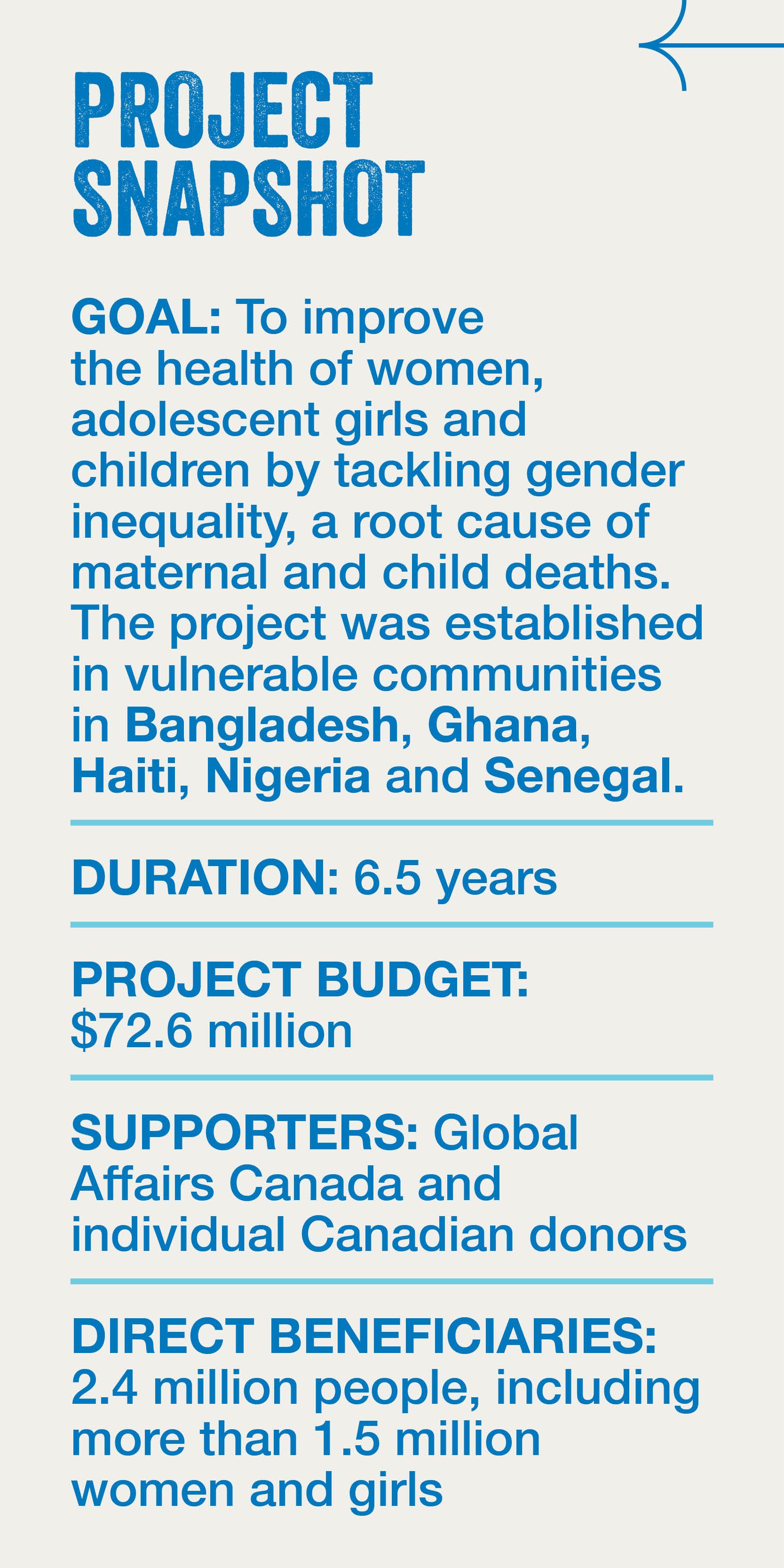

Plan International’s SHOW (Strengthening Health Outcomes for Women) project set out to improve the health of women, adolescent girls and children in rural communities in Haiti, Senegal, Nigeria, Ghana and Bangladesh.

Funded by Global Affairs Canada and individual Canadian donors, the project focused on addressing the root causes that lead to infant and maternal mortality.

Tackling gender inequality became the solution that set the project apart.

Ambulances and health equipment only go so far to prevent maternal mortality

Inequality creates the conditions; women’s health pays the price

Change for women and girls needs men and boys on board

Fabien is one of many young men promoting women’s and girls’ health in Haiti

In the communities where the SHOW project took place — communities like Fabien’s — many of the barriers that affect health care are concrete and tangible.

Families can’t afford medical expenses and the cost to travel to far-away health facilities. Health care workers don't have training or sufficient equipment to deal with complications during pregnancy or delivery. Women (and adolescent girls) deliver their babies at home without skilled supervision, and they face pregnancy without regular check-ups that would provide information on how to protect their health during and after pregnancy. There are no ambulances to transport patients during an emergency.

The SHOW project worked with communities to address these challenges through similarly concrete interventions: Equipment for health facilities and training for staff. Community savings groups to help fund medical costs. Providing ambulances — including bike and motorcycle ambulances where roads are inaccessible — and training for ambulance drivers.

But we knew that these solutions could only make lasting change if we also addressed the subtler, more intangible factors that affect access to health care — harmful gender norms.

Madame Badji is a midwife in Senegal. She’s working to change the harmful practices that contribute to maternal mortality.

The relationship between gender norms and poor health isn’t intuitive. But after more than a decade of delivering health projects that focus on reducing maternal mortality, Plan International has seen that the connection is incontestibleincontestable.

For example, complications during pregnancy and delivery are the greatest cause of death for adolescent girls globally, whose risk of facing complications is higher than older women. And the prevalence of adolescent pregnancy is intricately tied to gender norms that demand girls marry early or that deny them permission and information to make decisions about their bodies and sexual health.

Gender inequalities that see women as solely responsible for childcare and household labour are another example. The physical labour can endanger pregnant women’s health, and the burden of responsibilities makes it difficult to get away to attend check-ups that require long-distance travel.

Power dynamics at home also inform who has decision-making power and who controls the household finances, both of which are important for making women’s and girls’ health a priority.

Additionally, for adolescent girls, stigma around their pregnancy can make the very health services they need into a hostile and unwelcoming experience.

The SHOW project made addressing gender inequality the centre of its project design. It was woven through every aspect of the project, recognizing that the ability to make change through any individual intervention without it was limited.

“A traditional approach [to a maternal health project] would have been providing health centres with training and supplies as well as some education for the community,” explains Chris Armstrong, director of health at Plan International Canada. “With SHOW, we worked directly with communities to improve health by tackling gender barriers that have traditionally harmed women, men, girls and boys.”

Fabien is one of the many young men who got involved in the SHOW project.

Motivated by the loss he and his family experienced, Fabien joined his local health committee. In this community-led peer group members learn about and promote important information about maternal, newborn, sexual and reproductive health and rights.

“I explain to men how they can support their wives in pregnancy,” says Fabien. “I talk to them about the danger signs and I tell them about family planning, so that what happened to my mother does not happen to anyone else.”

Fabien's health committee is one of 1,315 that received SHOW support in the five project countries. Conversations about how men and boys can be champions for the rights and health of women and girls is an important part of the groups’ activities.

“The health-committee members do a tremendous job,” says Ms. Elizabeth, an administrator at a health centre in Haiti. “They have a lot of credibility and go to the most remote areas to educate people.”

In their own words

SHOW participants share how changing gender norms changed their lives

An innovative project set out to reduce infant and maternal mortality by reaching more than 1.5 million women and children in Haiti, Nigeria, Senegal, Bangladesh and Haiti. Its best solution for saving lives? Challenging gender norms.

SENEGAL

“Child marriage and early pregnancy are the two main challenges girls face in our community. A challenge for boys is that they lack information on sexual health and relations. That is why I’m a member of the Education for Family Life club.”

– Oumou, 19

Oumou, a 19-year-old woman, talks about her experience leading her community’s adolescent club, where they meet each month to discuss issues such as child marriage, teenage pregnancy and sexual and reproductive health and rights.

The SHOW project gave Oumou an outlet to spread important health information that is normally taboo to talk about.

BANGLADESH

“I used to feel ashamed to do my wife’s work because neighbours were critical,” admits Amirul, member of a Fathers Club. “Now, I am accustomed to doing the housework and neighbours don’t see it in a negative way. My family and I are very happy now.”

“I didn’t imagine that he could change. Now, he helps me, brings home water, takes our children to school and even cooks if I’m unwell.” – Laiju, married to Amirul

Amirul changed his mind (and his behaviour) after he joined the Fathers Club in Bangladesh. He says that after the discussions and training sessions, he began to challenge his ingrained negative attitudes toward gender equality.

A dad in Bangladesh

NIGERIA

Fatima, a member of a savings group in Nigeria, says the program helped her create a more equitable relationship with her partner. “Our VSLA helps us with savings, and it’s also a space [in which] to learn,” she says. “This improved my relationship with my husband. I used to do all the household chores, but now we share roles at home.”

“Due to training [I received] on danger signs in pregnancy, I observed swelling in my wife’s leg and knew it was a sign of danger. I rushed [her] to the hospital for treatment, and the group supported me with money from the fund.” – Alh Zaki Ckai, a savings group member in Nigeria.

Gender inequality lies at the core of many limitations to women’s health in Nigeria and many other countries. Challenging gender norms has to be part of the solution.

HAITI

“The ambulance didn’t take long to arrive. It saved my life and my son’s life.” – Nadia, 28

Plan International provided ambulances to the Haitian National Ambulance Center to save mothers’ and newborn babies’ lives.

Haiti has the highest maternal-mortality rate in the Americas, with 630 women’s deaths for 100,000 live births. Nadia, 28, experienced a complicated delivery while giving birth to her first child in 2021. The local health centre where she had been admitted couldn’t help her, so the ambulance took her to the hospital 70 kilometres away, where she received a Caesarean section.

GHANA

Village savings and loan associations (also known as VSLAs or savings groups) demonstrate what it means to be “stronger together,” says Chris Armstrong, director of health at Plan International Canada.

If a family is experiencing poverty, health care costs can deplete their income, leaving them unable to afford treatment in life-or-death situations. But when families combine their resources, they can lift each other out of the cycle of poverty that threatens their lives and livelihoods.

For Nanbos, who lives in Ghana, being a member meant he could help his sister when she needed it most.

“I took out a loan from my group’s fund to pay for services for my sister after she had a miscarriage. The doctors were able to save her life.” – Nanbos, a savings group member in Ghana.

Fabien is one of many young men promoting women’s and girls’ health in Haiti.

Savings groups create an opportunity to change power dynamics at home and in communities.

about SHOW's

gender champions

In 2022, the 6.5 year-long SHOW project came to a close. After directly reaching more than 1.5 million women and girls, the project communities saw marked improvements in health factors that are proven to be tied to infant and maternal health.

For example, SHOW tracked overall increases in:

• Mothers and babies who received postnatal care (PNC)

• The number of women receiving prenatal care four times during pregnancy

• The number of live births attended by health personnel

• The number of children vaccinated against Measles

• People who are aware of danger signs for pregnant women

“Postnatal care [PNC] is one of the hardest areas to improve and also one of the most important as it’s during this time that we lose mothers to severe bleeding and infection,” explains Dr. Tanjina Mirza, chief programs officer at Plan International Canada. “The improvement of 13% [seen by the SHOW project] in PNC suggests a real decline in mortality.”

From Haiti, Senegal, Bangladesh, Nigeria and Ghana - the results are in!

Watch the video to hear more about her story

read more

learn more

about how Plan International achieved these results

Getting to a health clinic is only half the battle

Changing attitudes within communities through groups like Fabien’s health committee was a critical step in getting women and girls the care they need. But norms also had to change at the health facilities themselves, so that patients could be sure they would find a safe and welcoming environment when they arrived.

Mavis is a community health worker at a local facility in Ghana that, she acknowledges, used to not to be a welcoming place for young pregnant women.

Mavis and other staff at her clinic participated in a training through SHOW that taught them how to provide emergency care during and after pregnancy, services they weren’t previously equipped to offer. It also emphasized the unique needs and challenges faced by adolescent girls seeking sexual and reproductive health care.

“I should give the same special treatment to adolescent girls that I give to adult women,” Mavis learned from the training. The SHOW project also made improvements at the health centre to increase privacy, such as installing partitions to separate patients and designating specific days for adolescents only.

Now, Mavis goes above and beyond to be a source of support and guidance for young women in her community. She counsels adolescents about delaying pregnancy and preventing sexually transmitted infections with contraceptives, and she speaks with their parents about creating a supportive environment in which these issues can be discussed openly.

By tackling stigma in communities and in healthcare, the SHOW project advocated for end-to-end change.

“I’ve never seen such comprehensive gender-transformative work,” says Tahina Rabezanahary, director of program management and compliance at Plan International Canada.

“We helped tackle the root causes by removing the barriers that prevent women and adolescent girls from accessing health care services and exercising their sexual and reproductive health rights. We also worked with men and boys to encourage them to be promoters of women’s and girls’ health and rights.”

Power and permission play a role in women’s health

Poverty is another major barrier to health, and one that also feeds — and is fed by — gender inequalities. Many families can't afford the medical and lost labour costs associated with giving pregnant mothers the care they need.

For girls’ health, the changes are starting

to show

These conversations are fundamentally changing gender dynamics in families and communities. With that change comes an increase in women’s and girls’ ability to seek the care they need to protect their health.

“Today, I see women who are going to deliver their babies at a health facility, and this is a big change,” adds Hafsatu Sety Sumani, who helped lead the SHOW project work in Ghana. “We see that men are supporting their pregnant wives more and accompanying them to the health facility.”

Ms. Raphael, a nurse in charge of a local community health centre in Haiti, says she has seen a considerable increase in the number of visitors to the centre in recent months.

“We used to receive only four or five visits a month,” she says. She used to feel discouraged by these low numbers. But now the number of people accessing the health centre has gone up significantly and there are around 50 visitors per month.

Aminata Traore Seck, from the Ministry of Education, Senegal said, “SHOW threw open the windows and let in a big breath of fresh air. The approach and changes were revolutionary.”

See how

Across Senegal, Haiti, Bangladesh, Ghana

and Nigeria, over

individuals in SHOW-supported VSLAs

(65% of whom are women) saved more than $750,000 in loans!

40,000

But gender inequality plays a role here too. With fewer opportunities to earn an income, women often hold less decision-making power at home. Male partners hold the power in financial decisions, but may not be well informed on maternal and child health concerns.

Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs) tackle both of these issues: They provide a financial resource for women to cover health care costs, and they provide training on gender equality and maternal health to men and women.

Applying a community-based microfinance model developed in Africa over 30 years ago, these groups help build savings to cover emergencies. They bring together 15 to 25 people who each contribute small amounts of money to create a shared pool of funds. They can then take small loans to cover things like health care expenses or even small-business start-up costs.

Led predominantly by women, these groups also help change the power dynamics in the household by giving them more financial agency and decision-making power.

Saadya Hamdani, director of gender equality at Plan International Canada, adds that they’ve seen the cascade effect of integrating gender equality into SHOW activities from start to finish. “As a result, we’ve seen changes in women’s community leadership and the ways in which men support women, both at home and when they’re seeking the health services they need,” Hamdani explains, “This is very exciting.”

SHOW responded to COVID-19

Madame Badji, a midwife in Senegal, explains how power dynamics at home were preventing women from getting vital care.

When the pandemic COVID-19 struck in 2020, the SHOW project was already deeply embedded in communities in Nigeria, Haiti, Senegal, Bangladesh and Ghana. This allowed us to act quickly to responded to ensure communities could still safely deliver critical care.